The Yukon Conundrum

I love the Yukon. I’ve been there twice courtesy of the Yukon Mining Association. We travelled by small plane, helicopter and huge SUVs driven at speed (looking at you Chris Ackerman) over gravel roads with killer potholes. Terrific place, wonderful people and dozens of compelling mining stories.

One of the striking things about my time in the Yukon was the efforts mining companies and the government put into First Nations relations. This was not performative; it reflected a genuine desire for partnership. And there are very sound economic reasons for this.

Just under 25% of the Yukon’s population of 47,000 are First Nations people. 37,000 of Yukoners live in Whitehorse, leaving around 10,000 in outlying areas. If a mining company wants a workforce, it only makes sense to hire and train local First Nations and that is exactly what has happened. Drill crews, road builders, camp kitchens and operating mines all employ First Nations people.

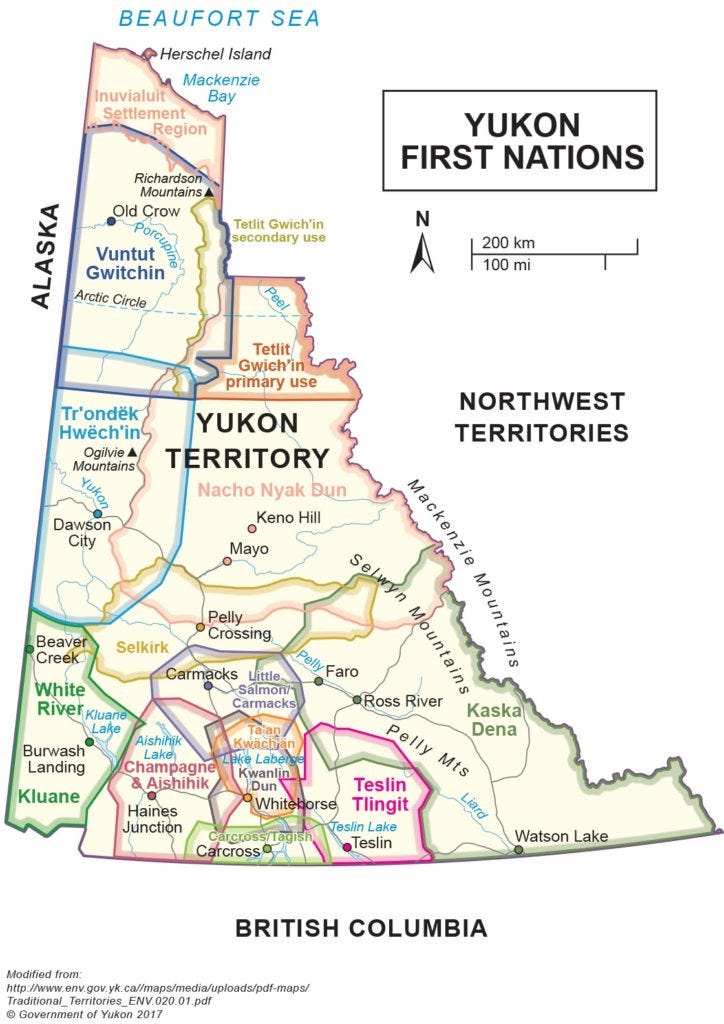

Mining and construction are the two key non-government sectors in the Yukon economy each contributing around 13% of provincial GDP. But mining and resource exploration and development are the overwhelming drivers of economic activity outside Whitehorse. And virtually all of these activities take place on land covered by First Nations treaties or claims. (Of the 14 First Nations in Yukon, 11 signed modern treaties between 1993 and 2005.)

In the wake of the Victoria Gold heap leach slide just over a year ago, Yukon First Nations generally, and the First Nation of Na-Cho Nyak Dun, where the Eagle mine was located specifically, called for action. Obviously, an investigation as to what went wrong and why but also an investigation into how the licencing system allowed Victoria to build its leach heap in, what turned out to be, an unsafe manner were necessary.

[An excellent summary of the Independent Review Board’s analysis of how the heap collapsed and the consequences of that collapse can be found at The Deep Dive. It is depressing reading.]

In response to the Eagle mine collapse, the Yukon government began a process to develop a framework in which to revise the legislation governing mining in Yukon. Some of the legal framework for mining is over a hundred years old and in desperate need of modernization. For the moment, the framework is confidential, as “it needs to be reviewed by the 14 Yukon First Nations and eight transboundary First Nations involved in the committee” said Yukon energy mines and resources minister John Streicker.

Enter the Conundrum. First Nation of Na-Cho Nyäk Dun Chief, Dawna Hope is quoted in the Yukon News as saying, “It calls for a question if Yukon public should accept a government that says it's committed to a Yukon First Nations and uphold our treaties. But then it continues to fall short behind closed doors of the confidential negotiations and they can't tell you anything of the details.”

Chief Hope backed up her Nation’s rejection of the framework with a Facebook statement,

A Yukon First Nation says it will oppose any new mining claims on its traditional territory as it begins a regional land-use planning process with the territory's government.

The First Nation of Na-Cho Nyak Dun says in a post on Facebook that it is issuing a notice to the mining industry that it will oppose any claim "through all available legal and political avenues."

The Nation says any such claim staked during the land-use planning process are "unwelcome" and "unlawful," citing past court decisions that it says "strongly discourages staking claims in the areas" undergoing such a process.

It says the Nation has adopted its own policy on mining that will govern the industry on its traditional territory while the planning process in pending.

There is a decent chance that the Na-Cho Nyäk Dun’s Nation’s position will be adopted by some or all of the other Yukon First Nations out of solidarity and concern. In which case, every exploration and development project in the Yukon will potentially be affected.

Balanced against that are the tremendous economic benefits of mining for both the First Nations qua Nations and First Nations individuals. When the Eagle mine closed Mayo, the center of the Na-Cho Nyäk Dun First Nation, went from nearly full employment to major unemployment. The Nation had just received its first payment from Victoria of over a million dollars.

The rejection of the legislative framework impairs every mining and exploration project in the Yukon, at least temporarily. It is, however, in the First Nations, the mining companies and the government’s interests to reach agreement quickly.

Balancing First Nations’ traditional and treaty rights against the huge economic gains which mining the billions of dollars worth of mineralized rock will require very real, transparent, negotiation. There are plenty of First Nations voices in favour of mining but the Eagle mine slide has shaken the confidence which the miners had worked for decades to create. Which, in turn, will complicate every Yukon mining project going forward. “Complicate” is not “cancel” but a meaningful, well funded, First Nations consultation process will have to be a part of exploration, development and actual mining. Most of the Yukon miners I’ve met would welcome just such a process.

(Disclaimer: I own shares in Yukon companies. This is not investment advice. Do your own due diligence.)

Thank you. Its good this is circulating now in the general public and with investors.

Just to note that the process for developing new mineral legislation and a strategy formally began in 2017 with an MOU with First Nations. https://www.yukon-news.com/news/yukons-draft-mineral-strategy-open-to-public-feedback-7000362